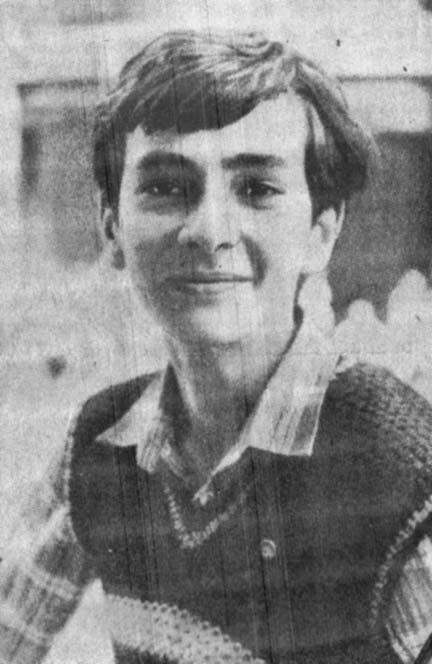

At the poetry school evening, Kolya Yaralov behaved somewhat unusually

And then from fragments, trivia, glances and a multiplicity of chance conversations a terrible truth came to light: he knew, he had prepared himself. It was as if he had cherished, and tenderly nurtured the idea of suicide for several months, even to the point of reverence. He cherished it like the last cartridge in a shoot-out.

From Kolya Yaralov’s will:

“I know what I’m doing. I know that I will cause you terrible grief. I feel sorry for you all but I feel even sorrier for myself. I must put an end to it all in time. Forgive me for everything. I have to solve this question… It’s a matter of honesty… I beg you, do not blame anyone for my death

Perhaps, I am committing an act of stupidity. To be honest, I do not want to die, but I want to continue to live even less…”

When a meeting of the teachers took place at the school, where Kolya’s death was discussed, his relatives heard the following words: “Your Kolya was too well-read and honest. He should have been brought up more toughly. He should have been better prepared for the difficulties in life…”

He used to love Bach and Beethoven and singing and playing the guitar. He loved poetry and Russian literature. He loved the mountains, and hikes on which he was first taken at the age of four.

From Kolya Yaralov’s diary: “What do I know of myself? I know five times more about myself than others. Yet I continue to discover more each day. On the whole, I am a reliable person. But nevertheless there is malice, cruelty and arrogance within me.

“What do I value in my friends and in people in general? In my friends I value understanding, and in people, nobility, purity, intelligence, cleverness, pride and honour…

“From childhood my favourite book was that of the Polish anti-fascist writer, Janusz Korczak ‘Król Maciuś Pierwszy’. I have read it about thirty times and still I am unable to keep back my tears at the end when Macius is dying…

“His ideas are close to me. The same ‘delirious’ thoughts of making the world a better place, and people purer…”

His aunt took Kolya to an arts centre. His adolescent works were soon exhibited and noted even by professionals. But then once he wandered into that room in the Palace of Young Pioneers where the Pioneer staff were meeting and became totally involved.

From a conversation with a classmate:

“You know, during recess he would always walk about with the book, Documents of 27th Congress.

“Did he just carry it about, just in case?”

“No, of course not, he used to read it…”

From his diary: “I would like to make the world a better place for everyone, but in a world where favouritism, the worship of money and power, and baseness and meanness rule, this is impossible.

“I have chosen a path of action via the Komsomol… Perestroika in the Komsomol League in our region has begun and has taken root, but of late, its pace has somewhat slackened…

“Some of our youth have a very scornful attitude towards our moral, spiritual and historical values. I am ashamed that I have to keep up relations with them in the Komsomol League… The role of the Komsomol as an educator has weakened…”

Kolya’s mother, in a fit of temper once said, “You have to be cured of the Komsomol!” He was most offended.

On another occasion he said to her, “Alright, mum, I won’t go to the Palace tomorrow, but on one condition that you also don’t go to the hospital, and leave your job!”

From the conversation with the secretary of the South-Ossetian Komsomol Regional Committee, Ariana Dzhioyeva:

“I remember he once turned up with the following idea

Is it because it is a “transitional age” that makes the incidence of suicides amongst teenagers so much higher? Yes, teenagers tend to succumb to the depths of depression and psychological stress. But something after all must hold him or her back from the edge, some kind of protective mechanism, an inner spiritual strength. The strange thing is that Kolya had this inner strength, he had faith, he was destined for great things, he had ideals…

From an essay by Kolya Yaralov: “It had become easier for Pavel[1]. He was struggling with real enemies. He wanted to give all he could to the freedom of humanity and towards the triumph of true humane values. I am prepared for such a struggle but the conditions for its realization do not exist. All my thoughts and ideas are pure fantasy if no one understands them. And I have no support and understanding.”

A strange boy? On the contrary, perhaps he is absolutely normal, perhaps too normal?

Everyone says that towards the end of the ninth grade, Kolya became totally indifferent towards voluntary social work. At the same time he went to the model Pioneer Camp, “Orlyonok”.

From Kolya Yaralov’s letter: “I found myself in my true element. I feel so energetic that I even think at night. We worked very intensively. A group of teachers from the Leningrad Pedagogical Institute worked with us. They were wonderful people! We felt as if we were two steps ahead of the vanguard of perestroika.

“I was selected as a representative of the All-Union Council of Assemblies. There are only 16 representatives throughout the country. I will be working in Transcaucasia.”

At last he had found a point of reference with whose help, it seemed, he could turn the world upside-down.

From a later letter to another participant of the Assembly: “I am in a bad mood at present. Our situation has become more exacerbated. All this distracts one’s attention from our work and things are turning out badly. After the initial giddy successes, we have run into a spell of bad luck. Everything that I have done is no good to anyone. There are no Komsomol members left. I am unable to interest them. A USSR wide rally of senior Komsomol members to celebrate the 70th Anniversary of the All-Union Komsomol League was a resounding success. We gave it our all but received nothing in return.”

From Kolya’s letter to Tanya Gavrilenko[2], youth leader of the “Orlyonok”:

“I am totally confused at present. Now that I am not in the Youth Camp I have begun to realize the degree to which life ‘there’ is idealistic and artificial, perhaps. After all that I see around me, there doesn’t seem to be any point to my work, or to ‘Orlyonok’ as it stands. What is the use of our work to anyone? After all, nobody can make anything out of this mess…”

In one of his last desperate letters Kolya wrote, “I have been unable to fulfil the duty with which I was entrusted. Now, my life is worthless…”

Then perhaps it is “Orlyonok” which is to blame? There in the youth camp conditions are ideal, there are sincere people of kindred spirit, comrades-in-arms, so to speak. Whilst here in the real world there are dull, routine working days. Someone called this Youth camp an “island of miracles”.

However, everyone has to decide for himself what is the norm

In the morning he rose, and calmly got dressed, got his things together. He took with him his cherished notebook about “Orlyonok” and the portrait of Napoleon which stood in a revered place in the bookcase. He left a cutting from a magazine about the suicide of the young poet, Alexander Bashlachev, on the table.

Napoleon… Bashlachev… This is his song: A collective farm water-carrier, hypnotized by a travelling magician had grand illusions that he was Napoleon. The hypnosis wore off, but the water-carrier remained in the Imperial frock-coat and could no longer live.

Who or what hypnotized Kolya?

Feats, suffering, heroic deaths

Examples of the fighters for a bright future are always at hand, and can be found in any school reader. But what of preachers and missionaries, pastors and doctors, and simply workers who through their labour and self-denial set an example of a humane attitude towards man? Perhaps they would have “convinced” Kolya…

“Differences and choices are not acceptable”

Abridged from KOMSOMOLSKAYA PRAVDA

[1] Pavel Korchagin is the hero of the novel, How the Steel was Tempered by Nikolai Ostrovsky, about Komsomol youth in the twenties and thirties.

[2] In original publication in Komsomolskaya Pravda: “From letter to Kolya from Tanya Gavrilenko, youth leader of the ‘Orlyonok’”